One afternoon in late autumn 2014 I found myself standing on a street corner in a steady fall downpour outside a post office in La Rochelle France, waiting for a friend to arrive. As people hurried by through the rain, I tucked up under the eve of the building’s roof, smoke from my pipe hanging in the damp air, and watched the faces in the crowd flowing along the tight pedestrian street. Significantly, I was dressed in the recreated clothing of a circa 1780 French Royal Navy sailor (see below), a wardrobe which consistently turns heads given its eccentric silhouette. That day however, one older woman in particular modestly looked me up and down as she came by along the narrow sidewalk; and then, after pausing for a second, she turned around back towards me. Striding up, she very genteelly leaned forward, touched my arm, and inquired in a very polite, curious, but animated tone, “What marvelous clothing! Is it some kind of ethnic dress – maybe some little village in the Balkans? Where are you from?!” As genuinely flattered as I was that this woman read my strange appearance as traditional rural clothing (and not just a cheap costume), and privileged that this interaction took place before tensions about refugees rose throughout Europe, this comment is just one instance of a larger issue which fascinates me – namely the ways in which people understand (or misinterpret) social and visual cues from historical clothing! Given the rather flamboyant subcultural fashion of late eighteenth-century sailors, this is something I encounter every time I wear recreations of historic maritime apparel in my living history work– and the following are a few overall themes I’ve gleaned from this experience, with anecdotes and reflection on what this means, both about seamens’ attire in the past and modern ideas about dress in the present.

Recreation of a sailor conscripted for service in Louis XVI’s Ponant fleet, c. 1780 (outside Cathedrale Saint-Louis de la Rochelle, 2015).

Of course, some of the visual cues I present in my dress are highly recognizable, even if the conclusions drawn are somewhat simplistic. For instance, knee-breeches and shoe buckles both instantly read to most audiences as ‘circa 1700s’ fashion, or at the very least ‘olde-timey’. However, people commonly assume that such buckles are somehow ‘fancy’, not just a ubiquitous consumer item or a general century-long fashion, and there is (understandably) a total disconnect over the specific detail of me wearing my shoe straps pulled down towards the toe ‘sailor fashion’ (see this detail in the paired upper images below). This is of course not to say that I expect general audiences to know or instantly memorize the endless nuances of long-extinct footwear trends from over two centuries ago, but rather to hopefully acknowledge that buckled shoes were once as ‘modern’ as shoes today, and that we will all one day become “Old Squaretoes” (i.e., dressing in the outdated styles of our youth – see an original example of this at bottom below).

One personal attempt to wear my shoe straps ‘sailor fashion’ (2016)..

Similarly, given the trope of curled white wigs in most pop culture depicting the eighteenth-century, both simple and more elaborately styled period hairstyles that I’ve worn (see photos below) immediately read as appropriately ‘historical’, especially when I am wearing recognizable ‘buckles’ (side-curls) by my temples and using recreated hair powder. But there is the persistent belief that period hairstyles always used wigs or that they were invariably grimey and pest-ridden, rather than the deeper acknowledgement that (just like today) hairdressing was as fluid as fashion, that styles of hair could send subtle social signals, that coiffures (false or natural) shifted greatly in style over time and space, and could be intrinsically part of good hygiene. If someone tugging on my tightly wrapped queue or gingerly taking a whiff of recreated 1779 hair powder is an entry point into the subtleties of this topic, then so be it, because such opportunities are then often gateways into a deeper discussion of the social and intellectual history behind such practices!

Recreated queued coiffure of a French Royal Marine, c. 1780. (Rochefort, 2016).

1770s hairstyle recreated with the assitance of Abigail Cox. (Williamsburg, 2015).

The uniformity or lack thereof in my depiction is something that equally draws a sliding scale of recognition. For instance when portraying a French Royal Marine, depending on the occasion, I’ll wear either the full dress ‘grand tenue’, fatigue ‘petite tenue’, or the more daily shipboard attire, (see the differences in each with the slide below). Even if audiences cannot immediately identify the kingdom or branch of service which this recreation depicts (visible to the careful observer in the naval buttons and the fleur de lys, anchor and other insignia used throughout), they instantly recognize that I am portraying a soldier, with or without me carrying my firelock, because the outfit is visibly a uniform and therefore looks ‘official’. By contrast, the shipboard work clothing of the Marine clothing (at right), let alone the ‘motley’ sailor’s attire I otherwise wear, is far less recognizable, and therefore commands strikingly less social presence. This dichotomy is then drawn into even sharper contrast on the few occasions where I have portrayed an officer, where rank and status is immediately visible to anyone by the higher quality materials of a uniform which includes a sword, gold braid, epaulettes, plumes, sashes, and other embellishments, besides the presence of an official entourage or soldiers (see bottom image below). Again, I do not expect the average tourist to be aware of long-defunct militaria, but I am simply fascinated by the way in which clothing (or a uniform) still does very much ‘make the man’ and the effect that one’s appearance, polished or otherwise, can have on the behavior of strangers.

Recreated 1781 meeting between the Marquis de Lafayette (played by Tristan Emerit) and General Washington (played by Ron Carnegie) at the Siege of Yorktown (Yorktown, Virginia, 2015).

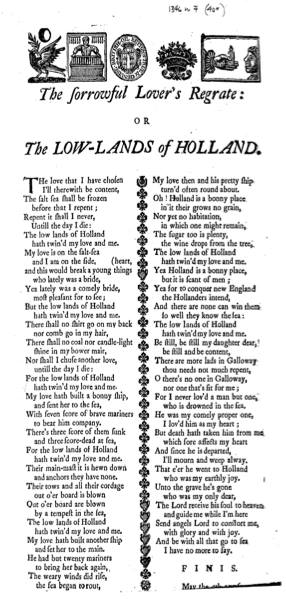

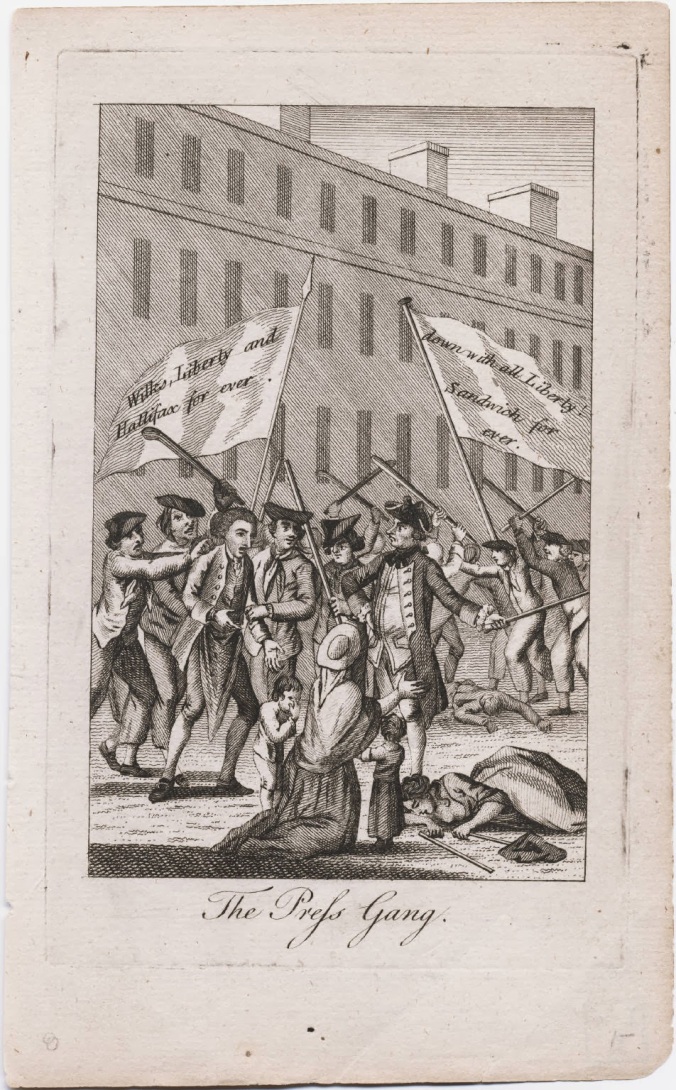

Other responses I’ve received from audiences are quite clearly conditioned by pop culture. For instance, whenever I wear a cocked hat (or ‘tricorn’), I instantly become a ‘pirate’, even if I am meeting visitors aboard a government warship – ideally, with sufficient social grace, this usually becomes an entry point into the economic warfare inherent in all eras of naval conflict, the legal boundaries of late eighteenth-century privateering, or alternately the way that popular media over the past two centuries has constructed a stereotypical image of ‘pirates’. In reality however, even ‘pirates’ simply dressed like the sailors they were, and would likely appeared both recognizably maritime and far more uniform than popular imagination envisions them today – so this in particular is a giant and persistent muddle which must be carefully unpacked with primary research !

Note the relative uniform appearance of the distinctive maritime ‘slop clothing’ worn by members of the recreated 1765 press gang of the HMS Maidstone (Newport, Rhode Island). [Credit to John Collins Photography]

For those select visitors who are familiar with the modern subculture of traditional sailing, my luggage is often a particular object of curiosity. Rather than the large canvas duffel bags and smaller ‘ditty bags’ (see an original example below, at right) which abound in collections of 19

th and 20

th-century maritime museums (but which have no concrete evidentiary basis for use before 1800), and are often copied by Tall Ships crewmembers as a way to display their seamanship, I use a hundred-liter cow-skin valise largely based on a 1786 French government ordonnance

[1] (see below, right). Whether it is a child in the airport or a senior pausing to visit my display, the fact that my bag (even if it’s not visibly luggage at first) is obviously made out of a cow is certainly a fruitful conversation starter!

And the passing similarities of my sailor attire with various folk costumes mean that I have been both mistaken in London’s Victoria Coach Station for a Spanish matador (given my short fitted jacket and square-topped 1780s-style round hat – see bottom left), and a Breton in regional costume (due to my petticoat breeches passing resemblance to traditional bragou braz – see bottom right).Alternately, the same simple red wool cap visible in my first photo (at top) has equally been assumed to be a revolutionary Phrygian cap, associated with 2013 lorry tax protests in Brittany, and elicited comparisons to both Jacques-Yves Cousteau and the Smurfs. So clearly, the responses of various audiences to my clothing are conditioned by their regional background, upbringing, and personality, things which can themselves be analyzed through the lens of history.

Recreated mid-1780s French sailor; not a matador!

Most frequently (and ironically) when I’ve done living history volunteering while studying in Scotland, my distinctive blue wool Scotch bonnet is mistaken for a French-style beret. This is understandable perhaps, given the stereotypical legacy of the 20th century ‘Onion Johnnys’ . However, in France this same beret is paradoxically seen as Scottish, (something potentially explained by the recent foreign success of the TV series Outlander)! Alternately, if I wear this same cap slanted to the side (incorrectly for this period, and an error perpetuated by the show), it immediately becomes more recognizably military to casual observers in both nations. And to muddle things further, the only textual reference I have found for a sailor specifically wearing a Scotch bonnet is from the memoirs of Samuel Kelly[2], a Royal Navy sailor who sailed to Scotland in 1783-84, but who was himself from Cornwall! Again, the goal is not to get newcomers entirely lost in such arcane details, but just to acknowledge that something as distinctive as a dicing pattern (below, at left), as unique as military insignia, or as simple as the presence (or lack) of a pompom can change the larger cultural associations of what is in reality just various cultural variants on the theme of a very basic knitted wool cap.

Note the tartan waistcoat and distinctive Scotch bonnet worn by the caricatured Scottish sailor at center in, Williams, Charles, ‘Makeing a Compass at Sea, or the Use of a Scotch Louse (caricature) ’ Tegg, Thomas (publisher), London, 1812, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, #PAG8606. Available at:

http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/127881.html Accessed: 18/11/2015

Still yet other sartorial cues result in audiences that I interact with struggling to connect the dots of clothing that was once iconic, but is no longer in use. For instance, the bold combinations of patterns shown in period visuals of sailors (often with contrasting stripes, checks, prints, and bold colors in abundance) often results in my modern viewers thinking that they are confronting a clown, a prisoner, or simply someone who is far too ‘colorful’ or flamboyant to be accurate to the eighteenth-century – even though such an ensemble would have been quintessentially maritime to any contemporary observer (see above left and bottom left). In similar fashion, the highly distinct woolen fringe on a specifically maritime ‘thrum cap’ usually elicits comparison to either “Rastafarian” or “yeti”, as viewers struggle to understand what they are seeing (see below right). And the baggy ‘seat’ of a pair of breeches or trousers, whose fullness allows the wearer to bend, squat, or sit in an otherwise well-fitted garment, typically elicits nervous laughter, teasing of ‘bubble butts’, or even furtive questions about diapers. Similarly, while sailors are nearly always depicted in contemporary art carrying sticks, carrying a cudgel today constantly perpelexes modern viewers, and draws analogies only to genteel Victorian walking sticks (see bottom left). And again, all this is to be entirely expected, and is something I’m equally guilty of when I myself engage with specialists of other periods outside my limited 50-year period of study – yet such interactions, however clumsy, are valuable ways to break the ice and transmit valuable information using historical dress as a visceral educational medium.

Note the stripes and sticks in the ‘shore-going rig’ of two recreated American merchant seamen, c. 1770s (Adam Hodges-LeClaire at left, Sean O’Brien at right), outside Old State House (Boston, Massachusetts (2015).

![todd-lacy A sailor wearing a thrum cap amongst other members of the recreated Charles Wilson Peale's company of 2nd Battalion Philadelphia Associators (Old Barracks Museum, Trenton, New Jersey, 2015) [Photo credit to Todd Lacy].](https://fishyfashion.files.wordpress.com/2016/11/todd-lacy.jpg?w=446&resize=446%2C296&h=296#038;h=296)

A sailor wearing a thrum cap amongst other members of the recreated Charles Wilson Peale’s company of 2nd Battalion Philadelphia Associators (Old Barracks Museum, Trenton, New Jersey, 2015) [Photo credit to Todd Lacy].

Most interestingly perhaps, audiences unanimously equate my grime-stained work clothing with authenticity (although it has equally led some to simply assume that I’m homeless). This popular notion, that everyone in the past was constantly and universally filthy, is greatly misleading, but understandable given its continued reinforcement by Hollywood and other various forms of popular history. Yet in reality, my clothing is not stained because it is pre-distressed or made up with theatrical products, but simply because I seek to do appropriate maritime work (tarring, painting, cleaning, eating, etc.) while wearing my period wardrobe, and seeing what additional understanding and empathy I can glean from it through this constant daily use. Of course, there is ample documentation for both ragged and well-dressed sailors, depending on context; but as a whole, it should be countered that humans in all eras, including historic mariners, strive to maintain their dignity and appearance whenever possible, just as I do today. And moreover I am fascinated by how this enthusiastic response from audiences towards my ‘grungy chic’ work-clothes speaks to the peculiarities of a modern world where designer jeans are bought pre-distressed, or where fast-fashion means that clothing is more disposable than ever before in human history.

“Before: the author and colleauge Jana Violante, fall 2014.

“After”: the same ensembles after two years of regular, practical use, fall 2016.

What then can be concluded from this rambling discussion of historic dress and the pitfalls and advantages of its modern perception?

- General audiences do recognize oddly specific details, authentic materials and overall effort, even when they don’t know what they’re looking at. Inversely, pandering to audiences pre-existing notions of what they think history looked like may be far easier in social terms, but ultimately less rewarding (and disingenuous).

- My biggest drive as a historic educator comes from un-teasing the nuances of historical apparel, and I am most enthused, not just when people recognize these subtleties in the clothing I wear, but when I can, moving from the micro to the macro, use such details to carry across more substantial pieces of historical analysis.

- Finally, there is no such thing as a bad question only a bad response on my part (beyond visitors socially clumsy or simply being rude). I am resigned to the fact that my most frequent questions will forever be “Aren’t you hot in that?” (or alternately, “aren’t you freezing” when it’s cold out…); but it is therefore my duty to think of creative ways to spin out all manner of questions, per the visitor’s interest, and create more fruitful exchanges about my own research and its relevance today.

As always though, please engage, comment, email, or post- tell me what you think!

[1] Mallard, ‘RÉGLEMENT Sur l’Ordre, la propreté & la salubrité à maintenir à bord des Vaisseaux, du premier Janvier 1786’, in Ordonnances et Reglemens, Concernant La Marine (Toulon, 1787). pp. 413-428, [valises specifically mentioned in Article 33, p. 420 and Article 36, p. 424.]

[2] Crosbie Garstin (ed.), Samuel Kelly: An Eighteenth Century Seaman Whose days have been few and evil, to which is added remarks, etc. of places he visited during his pilgrimage in the wilderness (New York, 1925). pp. 18, 80-84, 97, 103.

![a-dsc09243 [photo by Noel Heaney]](https://fishyfashion.files.wordpress.com/2016/12/a-dsc09243.jpg?w=314&resize=314%2C471&h=471#038;h=471)

![b-dsc09187 [photo by Noel Heaney]](https://fishyfashion.files.wordpress.com/2016/12/b-dsc09187.jpg?w=314&resize=314%2C471&h=471#038;h=471)

![todd-lacy A sailor wearing a thrum cap amongst other members of the recreated Charles Wilson Peale's company of 2nd Battalion Philadelphia Associators (Old Barracks Museum, Trenton, New Jersey, 2015) [Photo credit to Todd Lacy].](https://fishyfashion.files.wordpress.com/2016/11/todd-lacy.jpg?w=446&resize=446%2C296&h=296#038;h=296)

![David Allan, 'Fishwife', late 18th century, [#D404, National Gallery, Edinburgh].JPG](https://fishyfashion.files.wordpress.com/2016/11/david-allan-fishwife-late-18th-century-d404-national-gallery-edinburgh.jpg?w=330&h=441)

![Tattoos on the arms of sailors Tarantino, Louis Ducros, 1778 [RP-T-00-493-10C Rijks].jpg](https://fishyfashion.files.wordpress.com/2016/11/tattoos-on-the-arms-of-sailors-tarantino-louis-ducros-1778-rp-t-00-493-10c-rijks.jpg?w=336&h=826)